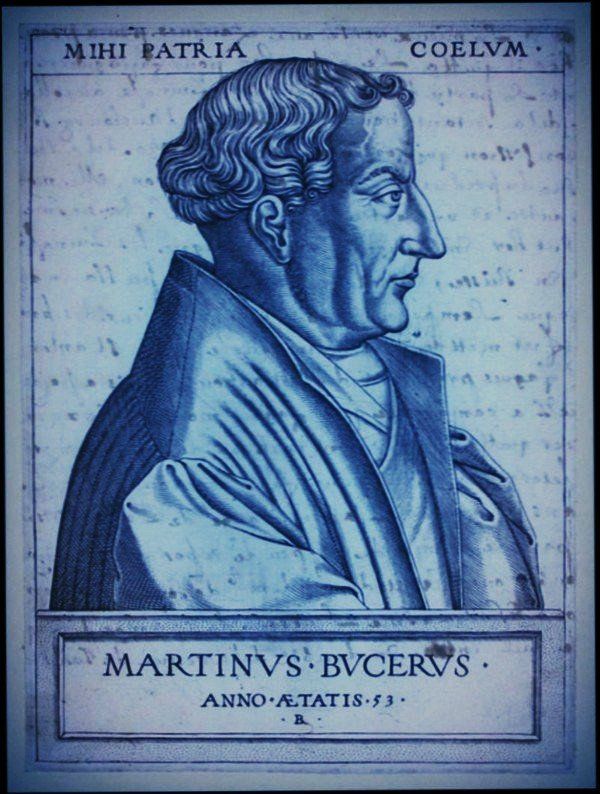

Martin Bucer, Marriage, & the Reformation (part 2)

PART 2

Continued from PART 1 ....

BUCER’S WRITINGS ON MARRIAGE & DIVORCE

Due to space and time I will briefly outline four areas of Bucer’s thought on marriage and related topics that are articulated primarily in his treatises Von der Ehe und Ehescheidung of 1533 (written to help the reform in Ulm on questions related to marriage – over 200 pages) and his last work De Regno Christi published of 1551. The four areas include the de-sacramentalizing of marriage, the denigrating of celibacy, a heightening of sinfulness, and elevating the companionable aspects of marriage above all other aspects of marriage.

First, Augustine set the ecclesial purposes for marriage in the 5th century; they were procreation, fidelity, and sacrament. Augustine’s third purpose of marriage as a sacrament evolved and increased in importance during the medieval period, in part because from the 7th century marriage under the purview of the church rather than the civil authorities. The concept of marriage as a sacrament was theologically and politically codified in canon law and this had made divorce nearly impossible while providing various complicated means for annulment (predominantly for the rich). At the same time obligatory clerical celibacy (though repeatedly contested) continued to elevate the celibate life over all other forms of life.

Bucer, with Luther and other reformers, rejected marriage as a sacrament. And in so doing they worked to undue the ecclesial authority over marriage by seeking to make marriage a civil arrangement. [1] Various Protestant territories quickly put together civil marriage courts. This transfer of authority of marriage to civil courts had radical consequences that have played out in today’s current system, for good or ill. Granted Luther, Bucer, and others could not see beyond Christendom.

Second, in addition to removing marriage from the sacramental list, the reformers attacked clerical celibacy. The obligatory celibacy of the priesthood was seen as evil by reformers. [2] Bucer held that “Before God no vow may be made or kept and no one may promise another person something or ask another to promise something if such a promise promotes evil or prevents the good or if that promise prevents the turning away from evil and the promotion of good.” [3] Hence, given the clear awareness of his own sexual fires and the common accusations of priestly sexual exploits, the vow to celibacy was illegitimate.

Likewise, Bucer believed that only around 1/1000 were given the actual gift of celibacy. [4] Therefore, because celibacy was an extremely rare gift from God, Bucer held that marriage should be compulsory for everyone. [5] As he stated in De Regno Christi , “unless God has clearly reserved another calling for a person—every man and every woman is called to marriage, and that a person may well be grateful to God for calling him or her to such an important estate.” [6]

The reformers did not reassign the celibate life so that it equaled the value of the married life, instead they repealed and replaced celibacy. Married life was superior to the single life. That such was the case can be seen by how Bucer held that a single person was only half a person. Selderhuis paraphrasing Bucer, states: “Only then one is a whole person, for all those who live outside of marriage, although God has not—on account of their nature by a special command—called them to a life without marriage, are only half humans. They are only half useful to society as well, and often they are altogether useless, and even harmful.” [7]

Contrary to the medieval West, marriage was for Bucer “the most important and highest sphere of life and from it all the others proceed.” [8] This was a radical shift, leading not only to the disparaging of the single life, but also resulting in the neglect of friendship as a legitimate and holy relationship. As Thomas Heilke demonstrates in his article, “Friendship in the Civic Order: A Reformation Absence”, the topic of friendship is blatantly absent in any of the writings or preaching of the reformers. Energy was focused on the topic of marriage and family, not firends.

The lacuna of friendship in Bucer’s thought (though he had many friendships) is seen in how he interprets the second greatest commandment, to love one’s neighbor. And according to him “Marriage offers the best opportunity to fulfill the law for ‘so also the whole law is fulfilled in loving one’s neighbor.’ … Hence the love of neighbor, which is most profoundly and perfectly expressed in the mutual love of marriage, causes us to remain in God.” [9] Likewise, marriage advances neighborly love because it generates more family members to love through in-laws and children. [10] The love of friends in Bucer is not considered in his nor in other reformer’s works, though all were familiar with Aristotle’s and Augustine’s treatments of friendship, among others. Within the nuclear family Jesus’ commands were now fulfilled at home.

Third, clerical celibacy was easily blamed as the root of immorality in the Church. The sin of sexual lust was so strong that to try and demand people to suppress it, was an act of evil. The hold of lust cannot be controlled and so, as Thomas Safley has said, the arguments for clerical marriage “took as their basic premise the degeneracy of human nature and the necessity of human sexuality. In this context the reason for extolling marriage was essentially negative; it served as a means of attacking the Catholic practice of clerical celibacy.” [11]

Fourth, While marriage was elevated as the highest form of relationship and one that every human person was naturally called to, so not to be inflamed with desire, the reformers adjusted the definition of marriage. Luther, Bullinger, and other reformers wished to keep procreation as a principle, though basically on account that its more important function was curbing sexual desire. Bucer, agreeing that marriage was important because it helped stop sin, nevertheless wanted to emphasize a more positive side of marriage, the way in which marriage fostered mutual love and service. [12] Bucer stated that “a real marriage exists only when there is harmony between the two partners and they so love each other that as a result the two become one.” [13] Hence a marriage is not a real marriage when love is gone, this he calls a ‘phantom marriage.’ [14] In this he was basically following Roman Law. So when Cranmer sought Bucer’s advice on the Book of Common Prayer , Bucer told him to move procreation to third place on the list and to raise mutual service as the first reason for marriage, which Cranmer did not change, but in the most recent book Bucer’s suggestion was implemented.

Fifth, and lastly, because of the importance of mutual love and service for a marriage, Bucer held that if it was not present in a marriage, divorce could be acceptable. Divorce was also acceptable for impotence, dementia, and forms of sickness that make fulfilling one’s conjugal duties impossible. As John Burcher, the English merchant mentioned in a letter to Bullinger, “In the matter of marriage Bucer is worse than permissive. One time, around the table, I heard him debate this issue when he stated that divorce should be granted on any ground, no matter how trivial.” [15] In fact, Bucer at times would talk about divorce as an instituted grace that allowed people to re-marry—since being single was susceptible to having lust run wild.

93 years after Bucer’s death in Cambridge, John Milton, who was dissatisfied with his marriage arrangement (his wife left him to move back in her mother’s house), translated 25 of Bucer’s chapters on marriage and divorce from he De Regno Christi , which Bucer had dedicated to the boy king Edward VI of England. Milton was translating these chapters in hopes to sway parliament in his favor, which was ultimately unsuccessfully.

Though Bucer’s thoughts on marriage and divorce were well discussed and known both in England and on the continent, his ideas were nowhere completely put into law, until the 20th century.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

This quick survey of Bucer’s ideas and experiences with marriage highlight how the reformation radically changed the practices of Protestant clergy in Europe. In promoting clerical marriage the reformers were elevating the institution of marriage while likewise disparaging singleness, so much so that the various protestant witch trials in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, targeted predominantly single women. Today singleness in the church continues to be seen as a failed or inferior estate than marriage, or in the word’s of Bucer – if you are single you are half of a person. In making marriage and the family the place where one fulfills the commandment of love of neighbor, as Bucer advanced, the concept of friendship and the love of a stranger also diminished. The only forms of intimacy that were being seen as legitimate and are legitimate in today’s church are the intimacies of marriage – i.e. sexual intimacy. No one wants to be a half-person, and everyone wants their relationship to be the best possible. Nobody asks, “Will you civil union me?” Thus same-sex intimate relationships for mutual service and companionship provide a context for the love of neighbor. Whereas this could have been a definition of friendship in the Medieval West, today it defines marriage. Hence, Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) and the complexities we face around marriage and its definition today.

[1] DRC 153, 180, Selderhuis, 28-29.

[2] Bucer following Luther held that vows were not valid: “Therefore no Christian is bound to vows invented by human beings, certainly not if these vows clearly constitute a hindrance to a life lived in accordance with God’s commandments. Such a vow, moreover, can hardly be called perpetual, for how could a person make a promise for all eternity when no one knows what God’s plan may be for his or her life, which is surely the case when that person is only fifteen, as Bucer himself was when he made this vow. The vows, accordingly, militate against the gospel in two ways: (1) by making a perpetual vow, a person is taking the control of his life into his own hands whereas all things are in God’s hands; and (2) he attempts thereby to earn heaven, whereas we receive heaven only on account of the merit of Christ” (BDS 1:170 in Selderhuis, 60-61).

[3] Selderhuis, 155.

[4] Early on Bucer “stressed in his preaching that the celibate life is a gift from God and cannot, therefore, be imposed arbitrarily on any person whatever as an obligation” (Selderhuis, 58 – this idea comes from BDS 1:143).

[5] “Marriage is implanted in humans by nature and, unless one has received the gift of chastity everyone is called to marriage. It is therefore both impossible and unnatural to prohibit marriage or to vow a solemn vow of perpetual chastity, for ‘nature remains nature.’ Among all peoples, which there fore includes non-Christian peoples, one observes the zeal that is applied to ensure that marriage will begin in the proper manner and to maintain it that way as well” (Selderhuis, 169). Again this view is coming from Selderhuis 171 looking at DRC 205 and Einf. Bed. 119b (full quote in footnote 49). In addition, Marriage is the most important institution: “Marriage is the most important and highest sphere of life and from it all the others proceed” (Selderhuis, 250-251).

[6] Selderhuis’s paraphrase on 171.

[7] (quote from Predig Buceri, 156a (TE, 222).” (Selderhuis, 173).

[8] (Selderhuis, 250-251).

[9] (Selderhuis, 171 – Einfältiges Bedenken (Cologne reformation work), 119b).

[10] Selderhuis, 171.

[11] Safley, “Marriage” in OER, 19.

[12] Selderhuis 258.

[13] (DRC 210) (Selderhuis, 265).

[14] (DRC 210) (Selderhuis, 265).

[15] John Burcher an English merchant in a letter to Heinrich Bullinger June 8, 1550 (quoted in Selderhuis, 1).