Martin Bucer, Marriage, & the Reformation (part 1)

PART 1

The following comes from draft of a paper I presented at conference Reformation Reverberations: Consequences and Challenges of Change

at APU commemorating the 500th anniversary of Luther 95 theses. My thoughts here are mostly dependent on the excellent study by Herman J. Selderhuis,

Marriage and Divorce in the Thought of Martin Bucer

, trans. by J. Vriend and L. Bierma (Truman State University Press, 1999).

I NTRODUCTION

The Obergefell v. Hodges 2015 Supreme Court Decision [1] is connected and a result of the reformation of marriage developed and strenuously debated by the 16th century Protestant Reformers. To briefly illustrate some of these connections I want to highlight how the discussion around marriage – particularly by Martin Bucer – can be seen as in line with America’s recent developments concerning marriage. With the legalization of same-sex marriage in the 21st century, the 16th century marriage reforms have come to full maturation, for better or worse. The 500th Anniversary of the Reformation is therefore something that not only Protestants should commemorate, but something that married members of the LGBT community can happily celebrate, for in many respects the reformer’s views of marriage, divorce, and celibacy paved the way to civil authorities granting same-sex marriages as a fundamental right.

This paper will briefly sketch these connections, primarily through the work of Martin Bucer, whose work on marriage and divorce were influential on the European continent but especially in England. I will proceed by first providing a short biographical sketch of Bucer’s life with an eye to our topic of marriage. Second, I will highlight some of his views on marriage that he expressed in his various writings on the topic. And lastly, I will provide some unrefined concluding thoughts.

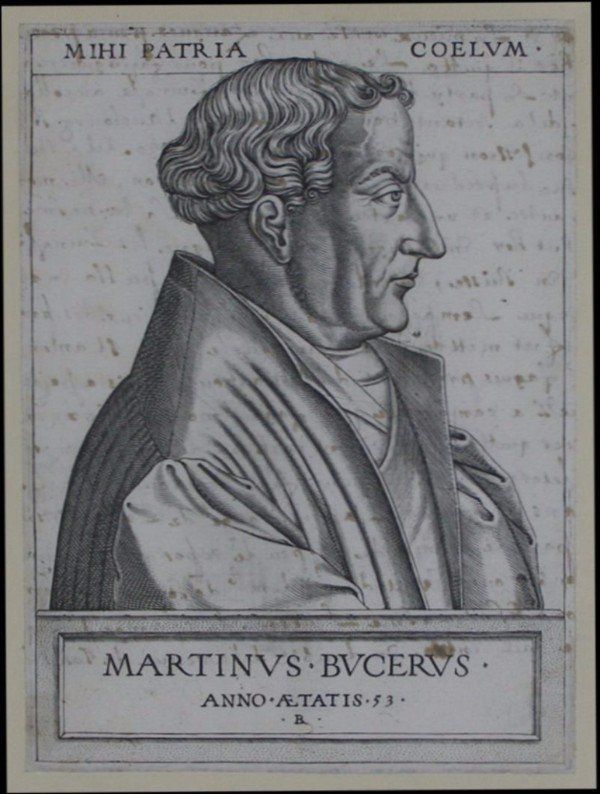

MARTIN BUCER

Who is Martin Bucer? Martin Bucer was born in 1491 in Alsace. He was a contemporary of Martin Luther and Ulrich Zwingli, part of the crew that we call the first generation of reformers. Bucer became responsible for the reforming efforts of Strasbourg. While leading the reform there he mentored the young John Calvin and spent countless hours as a mediator between the Swiss reforming camp and Luther’s German reforming camp.

Bucer began his ecclesial career as a Dominican monk, but after meeting Luther and reading his popular tracts of 1521, Bucer decided to leave the Order and broke his monastic vows. He then, quickly found a runaway nun, Elizabeth Silbereisen, and got married in the Summer of 1522 (following only Karlstadt and Zwingli ( secretly ) in this move toward clerical marriage). From that point on he was writing on marriage, divorce and celibacy, while also negotiating marriages and re-marriages. Having experienced marital bliss himself (and no doubt dousing his burning sex drive) he was zealous to have others share the blissful estate and so he invested time brokering marriages. That we know he successfully arranged the marriages of Wolfgang Capito, Conrad Hubert, John Calvin, Bartholomew Fontius, Paul Phyrgio, Christoph Söll (to his stepdaughter), Guillaume Du Molin, among others. If you were single and an acquaintance of Bucer, he had a plan for your life. In 1542 Elizabeth arranged for Bucer to marry his friend’s widow as she herself was dying. So upon her death Bucer remarried the widow of Wolfgang Capito, Wibrandis Rosenblatt, who has been affectionately nicknamed the Reformation Frau or The Bride of the Reformation, because Bucer was her fourth reforming husband following Ludwig Keller, Johannes Oecolampadius, & Wolfgang Capito. In addition to these experiences of marriage and remarriage Bucer became a key negotiator in political marriage affairs; predominantly the affairs of Henry VIII (where his opinion was requested) and the marital desires of Philip the Landgrave of Hesse.

In regard to Henry VIII’s situation, Bucer first suggested that the King take

on a second marriage, that is, practice bigamy. However, in subsequent letters

he asserted that if a bigamous arrangement would not be possible the king’s

disturbed conscience could be used to demonstrate the breakdown of the marital

union rendering it illegitimate, since if the conscience of the king was clear

the marriage would be legitimate. [2]

As we will see continuing affection is an important pillar underlying Bucer’s

understanding of marriage. [3]

In the situation with the Landgrave, Bucer met with Philip and wrote up a defense of bigamy. This defense gave Philip the confidence to get a second wife. Bucer and Melanchthon attended the wedding. A primary argument for allowing Philip more than one wife was that because marriage was meant to help curb sexual desire and avoid fornication, if sexual desire was not being squelched within the first marriage then taking on a second wife allowed a man to continue to curb his yearning loins without committing fornication. If he were not allowed to remarry he would be in a place where committing adultery was a strong possibility. Herman J. Selderhuis summarizes Bucer’s view, thus: “God would rather allow a certain evil to thereby avoid a worse evil. To have more than one wife is certainly evil but to have an extramarital relationship is a greater evil and even more destructive of marriage.” [4] Now it should be noted that Bucer was not alone in allowing the Landgrave a bigamous solution, in this he was in agreement with Luther and Melanchthon, amongst others. It should also be noted that bigamy was illegal and punishable by death in the empire, and thus this arrangement eventually put the Landgrave, who was one of the most powerful Protestant princes, on unstable political footing – He would eventually sign the emperor’s Augsburg interim to save his neck. [5]

This brief biographical sketch minimally demonstrates that for Bucer and other Reformers, Marriage, Divorce, Re-Marriage, and Bigamy were at the heart of the Reformation (pun-intended). What Bucer wrote on the subject of marriage will help us understand why and how he and others played with marriage the way they did.

[1] Here are some key aspects of Justin Robert Kennedy’s opinion: “The nature of marriage is that, through its enduring bond, two persons together can find other freedoms, such as expression, intimacy, and spirituality. This is true for all persons, whatever their sexual orientation.” (576 U.S. __ 2015, 13). And “A second principle in this Court’s jurisprudence is that the right to marry is fundamental because it supports a two-person union unlike any other in its importance to the committed individuals. … Marriage responds to the universal fear that a lonely person might call out only to find no one there. It offers the hope of companionship and understanding and assurance that while both still live there will be someone to care for the other” (576 U.S. __ 2015, 13-14).

[2] Selderhuis 145-148. Bucer’s first thought to Simon Grynaeus’s search for support (on behalf of the king) was that second marriage might be better: “Bucer therefore thought it better to permit Henry a second marriage while maintaining the first, at least if the queen could agree to this arrangement. In that case, henry would be obligated to continue to honor her as queen and to love her as a wife. … In adopting to this position he was agreeing with Luther who in this situation preferred bigamy to dissolution as well” (Selderhuis, 141). (and since Catharin of Aragon was the cousin of the Emperor). Bucer does however appeal to conscience as a way out: “In a third letter Bucer repeated that, according to the letter of the law, the marriage between Henry and Catherine was in fact illegitimate. The marriage would be illegitimate if Henry’s conscience were unencumbered. Bucer’s appeal to the absence of clear conscience apparently meant for him that in that case the law might have been violated. The conscience constitutes a domain of its own where in exceptional situations violations of God’s law can be justified before him (Selderhuis, 142).

[3] Selderhuis, 141-142. See on his view of affection page 154 in regard to Philips marriage and page 167.

[4] Selderhuis, 154.

[5] Bucer supports Philip of Hesse’s desire to take a second wife. He predominantly takes up this position in his book Argumenta Buceri Pro et Contra. Arguments for bigamy: “Because one motive for marriage is avoidance of fornication, this is probably also the argument for the fact that the patriarchs had more than one wife” (Selderhuis, 154). A marriage where love is lacking is no marriage at all: “As an example of a situation which something evil has to be chosen to avoid a greater evil he mentions divorce. A divorce that is not occasioned by adultery, after all, while also wrong, is nevertheless permitted, for a marriage in which love is lacking is no longer a marriage. In such cases God would rather have a divorce take place than that a husband and wife remained in a matrimonial relationship without love and so sinned even more seriously against marriage. … God would rather allow a certain evil to thereby avoid a worse evil. To have more than one wife is certainly evil but to have an extramarital a relationship is a greater evil and even more destructive of marriage” (154). Against marriage vows: “To the objection that bigamy is in conflict with the marriage vow Bucer gave the same answer he used with respect to priestly or monastic vows: ‘Before God no vow may be made or kept and no one may promise another person something or ask another to promise something if such a promise promotes evil or prevents the good or if that promise prevents the turning away from evil and the promotion of good’” (Selderhuis, 155). Bucer and Melanchton are present at the wedding on March 4, 1540. Bucer, Luther, Melanchthon, Brenz, Osiander, and Ambrose Bluarer all assented to the bigamous solution.